Bobby Sherman, whose winsome smile and fashionable shaggy mop top helped make him into a teen idol in the 1960s and ’70s with bubblegum pop hits like “Little Woman” and “Julie, Do Ya Love Me,” has died. He was 81.

His wife, Brigitte Poublon, announced the death Tuesday and family friend John Stamos posted her message on Instagram: “Bobby left this world holding my hand — just as he held up our life with love, courage, and unwavering grace.” Sherman revealed he had Stage 4 cancer earlier this year.

Sherman was a squeaky-clean regular on the covers of Tiger Beat and Sixteen magazines, often with hair over his eyes and a choker on his neck. His face was printed on lunch boxes, cereal boxes and posters that hung on the bedroom walls of his adoring fans. He landed at No. 8 in TV Guide’s list of “TV’s 25 Greatest Teen Idols.”

He was part of a lineage of teen heartthrobs who emerged as mass-market, youth-oriented magazines and TV took off, connecting fresh-scrubbed Ricky Nelson in the 1950s to David Cassidy in the ’60s, all the way to Justin Bieber in the 2000s.

Sherman had four Top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 chart — “Little Woman,” “Julie, Do Ya Love Me,” “Easy Come, Easy Go,” and “La La La (If I Had You).” He had six albums on the Billboard 200 chart, including “Here Comes Bobby,” which spent 48 weeks on the album chart, peaking at No. 10. His career got its jump start when he was cast in the ABC rock ’n’ roll show “Shindig!” in the mid-’60s. Later, he starred in two television series — “Here Come the Brides” (1968-70) and “Getting Together” (1971).

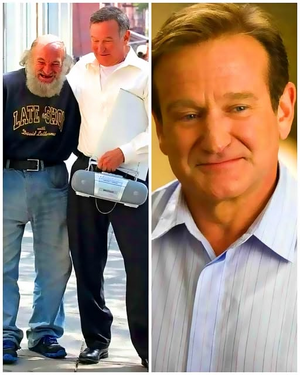

Bettmann

Pop star and TV actor Bobby Sherman

After the limelight moved on, Sherman became a certified medical emergency technician and instructor for the Los Angeles Police Department, teaching police recruits first aid and CPR. He donated his salary.

“A lot of times, people say, ‘Well, if you could go back and change things, what would you do?’” he told The Tulsa World in 1997. “And I don’t think I’d change a thing — except to maybe be a little bit more aware of it, because I probably could’ve relished the fun of it a little more. It was a lot of work. It was a lot of blood, sweat and tears. But it was the best of times.”

Sherman, with sky blue eyes and dimples, grew up in the San Fernando Valley, singing Ricky Nelson songs and performing with a high school rock band.

“I was brought up in a fairly strict family,” he told the Sunday News newspaper in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1998. “Law and order were important. Respect your fellow neighbor, remember other people’s feelings. I was the kind of boy who didn’t do things just to be mischievous.”

He was studying child psychology at a community college in 1964 when his girlfriend took him to a Hollywood party, which would change his life. He stepped onstage and sang with the band. Afterward, guests Jane Fonda, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo asked him who his agent was. They took his number and, a few days later, an agent called him and set him up with “Shindig!”

Sherman hit true teen idol status in 1968, when he appeared in “Here Come the Brides,” a comedy-adventure set in boom town Seattle in the 1870s. He sang the show’s theme song, “Seattle,” and starred as young logger Jeremy Bolt, often at loggerheads with a brother, played by David Soul. It lasted two seasons.

Following the series, Sherman starred in “Getting Together,” a spinoff of “The Partridge Family,” about a songwriter struggling to make it in the music business. He became the first performer to star in three TV series before the age of 30. That television exposure soon translated into a fruitful recording career: His first single, “Little Woman,” earned a gold record in 1969.

“While the rest of the world seemed jumbled up and threatening, Sherman’s smiling visage beamed from the bedroom walls of hundreds of thousands of teen-age girls, a reassuring totem against the riots, drugs, war protests and free love that raged outside,” The Tulsa World said in 1997.

His movies included “Wild In Streets,” “He is My Brother” and “Get Crazy.”

Sherman’s pivot to becoming an emergency medical technician in 1988 was born out of a longtime fascination with medicine. Sherman said that affinity blossomed when he raised his sons with his first wife, Patti Carnel. They would get scrapes and bloody noses and he became the family’s first-aid provider. So he started learning basic first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation from the Red Cross.

“If I see an accident, I feel compelled to stop and give aid even if I’m in my own car,” he told the St. Petersburg Times. “I carry equipment with me. And there’s not a better feeling than the one you get from helping somebody out. I would recommend it to everybody.”

In addition to his work with the Los Angeles Police Department, he was a reserve deputy with the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, working security at the courthouse. Sherman estimated that, as a paramedic, he helped five women deliver babies in the backseats of cars or other impromptu locations.

In one case, he helped deliver a baby on the sidewalk and, after the birth, the new mother asked Sherman’s partner what his name was. “When he told her Bobby, she named the baby Roberta. I was glad he didn’t tell her my name was Sherman,” he told the St. Petersburg Times in 1997.

He was named LAPD’s Reserve Officer of the Year for 1999 and received the FBI’s Exceptional Service Award and the “Twice a Citizen” Award by the Los Angeles County Reserve Foundation.

In a speech on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives in 2004, then-Rep. Howard McKeon wrote: “Bobby is a stellar example of the statement ‘to protect and serve.’ We can only say a simple and heartfelt thank you to Bobby Sherman and to all the men and women who courageously protect and serve the citizens of America.”

Later, Sherman would join the 1990s-era “Teen Idols Tour” with former 1960s heartthrobs Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones of the Monkees and Peter Noone of Herman’s Hermits.

The Chicago Sun-Times in 1998 described one of Sherman’s performances: “Dressed to kill in black leather pants and white shirt, he was showered with roses and teddy bears as he started things off with ‘Easy Come, Easy Go.’ As he signed scores of autographs at the foot of the stage, it was quickly draped by female fans of every conceivable age group.”

Sherman also co-founded the Brigitte and Bobby Sherman Children’s Foundation in Ghana, which provides education, health, and welfare programs to children in need.

He is survived by two sons, Christopher and Tyler, and his wife.

“Even in his final days, he stayed strong for me. That’s who Bobby was — brave, gentle, and full of light,” Poublon wrote.