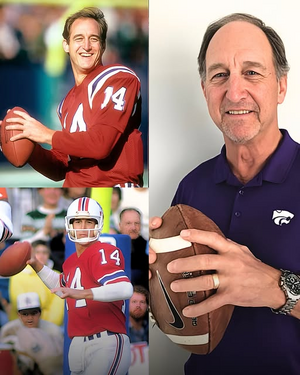

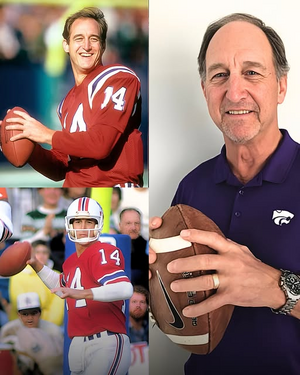

Grogan arrived in New England in 1975 without ceremony, a fifth-round pick, 116th overall, easy to overlook on draft weekend. What followed was anything but quiet. From the moment he stepped into the Patriots’ locker room, he was forced to fight — not just opponents, but expectations, injuries, and a revolving door of quarterback controversies that never truly stopped. Yet early in his career, one thing stayed constant: when Grogan was healthy, he played, starting every game for four straight seasons and carving out an identity that was uniquely his.

As a rookie, he didn’t wait long for his chance. Grogan played 13 games in a 14-game season and started seven of the final eight, taking the job from former Heisman Trophy winner Jim Plunkett. The numbers were raw — 1,976 passing yards, 11 touchdowns, 18 interceptions — and the Patriots finished 3–11. But there were flashes. In Week 8, against Dan Fouts and the San Diego Chargers, Grogan earned his first career win, throwing for 285 yards and a touchdown in a 33–19 victory. By the offseason, Plunkett was gone. The franchise had chosen its direction.

Everything changed in 1976. Grogan didn’t just quarterback the Patriots; he powered them. He accounted for 30 total touchdowns, attacking defenses through the air and on the ground, and led New England to an 11–3 record — the best season in franchise history to that point and its first playoff berth since 1963. The Patriots stunned the defending Super Bowl champion Steelers, then humiliated the Raiders 48–17, handing Oakland its only regular-season loss. Though the season ended with a narrow 24–21 playoff loss to those same Raiders, Grogan had announced himself to the league.

He rewrote expectations of what a quarterback could be. In 1976, he rushed for 12 touchdowns, breaking a record held by Tobin Rote and Johnny Lujack. The mark stood for 35 years until Cam Newton finally passed it in 2011. Grogan also led all quarterbacks in rushing yards with 397. On October 10, against the Jets, he made Patriots history by becoming the first quarterback in franchise history to rush for more than 100 yards in a game, slicing through New York’s defense in a 41–7 rout. It wasn’t improvisation — it was intent. Grogan ran because it worked, and because defenses couldn’t stop it.

The legs kept moving in 1977. Grogan rushed for more than 300 yards again, though the touchdowns shifted to a powerful stable of running backs — Horace Ivory, Sam “Bam” Cunningham, and Andy Johnson. That season also marked the arrival of Stanley Morgan, a first-round rookie who quickly became Grogan’s favorite target. Their chemistry felt natural, almost inevitable, and by the time both careers ended, they would stand as the most productive quarterback-receiver duo in Patriots history. The team slipped to 9–5 and missed the playoffs, but Grogan still finished atop the league in quarterback rushing yards for the second straight year.

In 1978, New England surged again. Grogan threw just shy of 3,000 yards, scored 20 combined touchdowns, and led the Patriots to an 11–5 record, a division title, and the franchise’s first-ever home playoff game. Though that postseason debut ended in a 31–14 loss to the Houston Oilers, the season left its own mark on history. The Patriots rushed for 3,156 yards — an NFL team record at the time — with Grogan contributing 539 yards and five touchdowns himself. Four players on that roster rushed for over 500 yards, something no other NFL team has ever matched. Once again, Grogan led all quarterbacks in rushing.

Statistically, 1979 was Grogan at his peak. He threw for 3,286 yards and 28 touchdowns, tying Cleveland’s Brian Sipe for the league lead, while still adding 368 rushing yards and two scores. For the fourth consecutive season, no quarterback ran for more yards than Grogan. Against the Jets that year, he delivered the finest game of his career — 315 passing yards, five touchdowns, no interceptions, plus 45 yards rushing — in a brutal 56–3 demolition. Yet football has a way of undercutting even its best performances. Defensive breakdowns haunted New England, and despite Grogan’s production, the Patriots finished 9–7 and missed the playoffs.

The early 1980s brought a harsher chapter. Injuries piled up, particularly to his knees, stripping away the mobility that once defined him. Grogan split time with Matt Cavanaugh as the Patriots stumbled through lean seasons, including a disastrous 2–14 campaign in 1981. The quarterback who once punished defenses with his legs was forced into the pocket, uncomfortable, constrained, adapting on the fly. The team returned to the playoffs only once during that stretch, in the strike-shortened 1982 season.

Pressure mounted again in 1983 when New England drafted Tony Eason in the first round. Grogan responded the only way he knew how — by competing. He threw 15 touchdowns that season and showed flashes of the old resilience, but the following year told a different story. After a 1–2 start in 1984, with Grogan struggling badly in two early losses, Eason took over as the primary starter.

Somewhere along the way, another symbol appeared. After suffering a neck injury, Grogan began wearing a thick neck roll — a piece of equipment that soon became inseparable from his image. It wasn’t cosmetic. It was survival. Like much of his career, it reflected a quarterback who refused to disappear quietly, even as the game demanded more from his body than it ever gave back.

Grogan’s early years weren’t clean or perfectly scripted. They were bruising, volatile, and often unfair. But they told the story of a quarterback who reshaped expectations, carried a franchise through its first real highs, and kept standing long after the hits began to take their toll.